Kate Alexander Shaw

Narrating the economy: can Starmer and Reeves bring coherence back to UK economic policy?

Feb 14, 2026

Governments need an economic policy narrative that can organise their ideas, stabilise uncertainty and provide a framework for making and explaining their policy choices. Since 2016, economic policy in the UK has lacked any coherent narrative. Starmer and Reeves have now set out their diagnosis of the UK’s problems, but as long as Labour’s economic policy is driven primarily by their fiscal rules, the link from diagnosis to policy prescriptions will be broken.

It is an uncomfortable fact of life for economic policymakers that they must operate against a backdrop of perpetual uncertainty. Data are contradictory, indicators compete against one another for attention, and the lagged effects of policy can take years to work through. Economic uncertainty, however, is politically dangerous; both voting publics and financial markets are looking for reasons to be confident that the government knows what it is doing. The key mechanism by which governments resolve this tension is through the construction of narratives that distil economic complexity into a set of core propositions that can be a stable basis for policy. Before the election, Labour had begun to set out their own narrative of the economy. But is it enough to move the UK out of a period of stagnation and policy incoherence? Answering that question means looking more closely at what economic narratives are for, and what they do.

The dual role of economic narratives

The political scientist Vivien Schmidt draws a distinction between the two functions of political discourses: coordination, which is about the backstage conversations between key actors, and communication, which is public.1 Understood in these terms, narratives are not just a set of talking points for the purposes of a comms strategy; they have a prior function as coordinative frameworks within which governments may organise their ideas in the first place. These coordinative processes then assemble what Deborah Stone calls a ‘causal story’ – an account that knits together a diagnosis of what is wrong, a prescription of what should be done about it, and a prediction about what will change if those policies are enacted.2

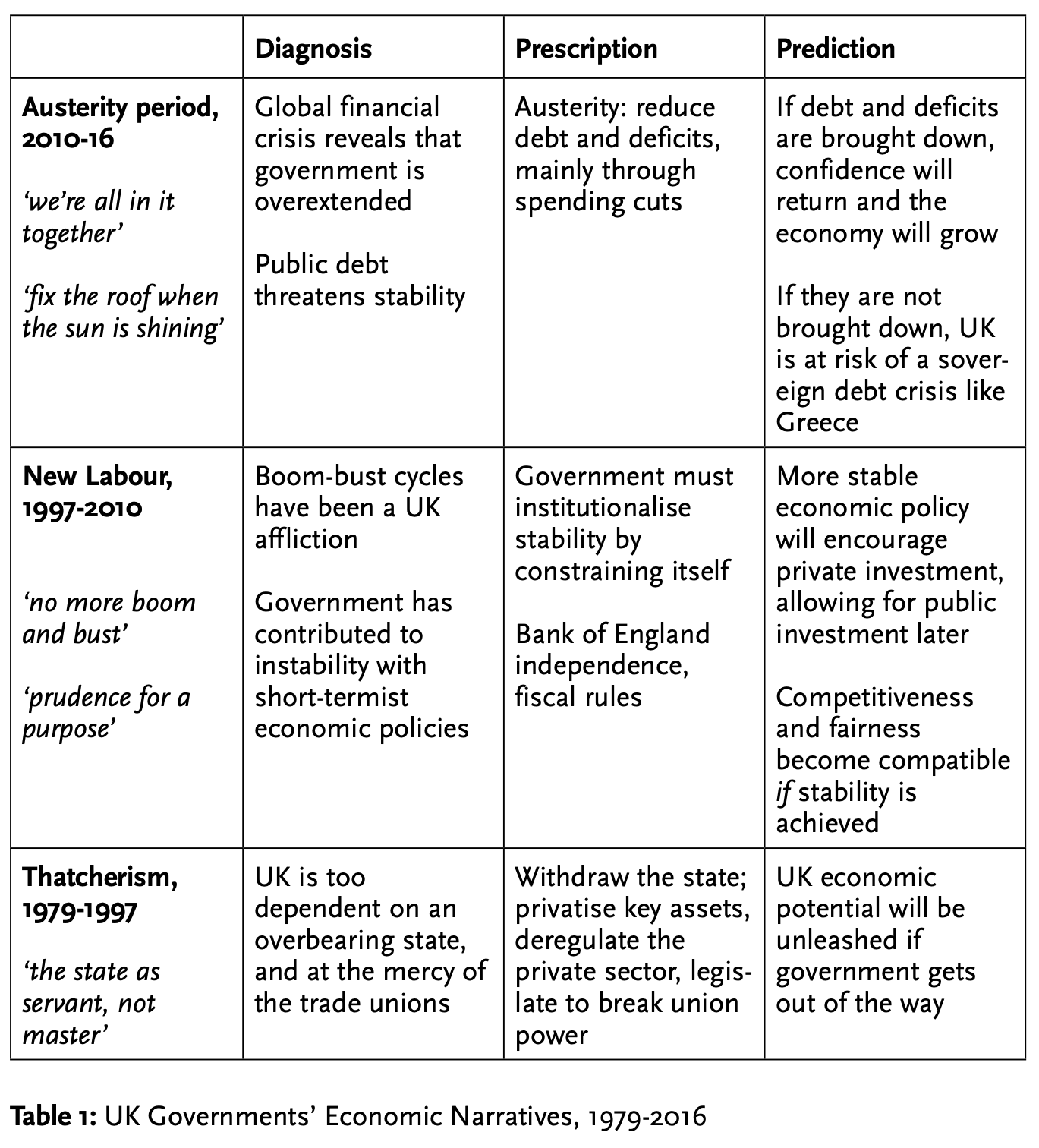

These three elements of diagnosis, prescription and prediction, can be clearly identified in the economic strategies of successive UK governments (Table 1 below). The economic policies of the Thatcher governments in the 1980s were, of course, connected to broader currents in economic thought at the time, particularly the rise of monetarism and the suite of ‘neoliberal’ policy that became influential across the English-speaking democracies. Distilled into a narrative, the Thatcherite diagnosis was of a country in which the state had become overbearing, leaving both businesses and households overdependent on public support, and private enterprise stifled. The signature policies of that era – deregulation, privatisation, anti-union legislation – followed from that diagnosis. The prediction, then, was that a liberated private sector could become the engine of British revival.

The New Labour government had its own diagnosis of Britain’s problem: stop-go cycles of overheating followed by a slump, driven partly by short-termism in government policy. The prescription then followed: boom and bust could be defeated by institutionalising stability through Bank of England independence and fiscal rules. That being done, confidence would be embedded and growth would follow, generating the revenues to pay for social programmes that would deliver fairness without hurting competitiveness.

The post-crash austerity narrative of the Cameron governments also worked from a simple diagnosis: that the key risk to stability after the financial crisis was public debt, so that reducing deficits should be the first priority of government. George Osborne’s Treasury drew on then-fashionable theories to suggest that fiscal contractions could in fact generate growth, but even that was a secondary goal compared with shrinking state spending and driving down debt. The prediction in the austerity narrative was therefore double-edged: fiscal tightening might well deliver growth, but even if it did not, a failure to trim back spending would expose the UK to the risk of a sovereign debt crisis, to be avoided at all costs.

There is no space here to debate the merits of these narratives, and indeed they have been well rehearsed elsewhere. The point is that narratives are necessarily selective, prioritising certain dimensions of the economy and dispensing with others. Each of the narratives described here is self-evidently imperfect, with particular blind spots. Thatcherism lionised private sector activity at the expense of unemployment and inequality. New Labour insisted that institutionalising openness to globalisation could deliver public goods (or at least the revenues to pay for them) but neglected the potential for systemic risk and asset inflation in their financialised growth model. Austerity narrowed the lens to fiscal outputs, either trusting that positive economic outcomes would follow or judging that they were secondary to the main goal of adjusting the state. But what each of these narratives shared was a strong connection between the diagnosis and the prescription; an internal logic which could guide and legitimise policy decisions. It was precisely by being selective, and making the case for a particular reading of the economic challenges facing the country, that these narratives allowed governments to identify and focus on their key priorities. Narrative frameworks provided a structure within which subsequent policy choices made sense, and policy trade-offs could be justified.

It is this coordinative work which then sets up the public communication of the narrative. Having assembled a set of economic ideas that make sense of the economic conditions, a coherent narrative allows a government to stake a claim to the national common sense, shaping the public’s understanding of what is wrong with the economy, and selling the choices and trade-offs that will follow. Fourteen years on from George Osborne’s first budget, austerity has become a dirty word in British politics, but it is worth remembering that during the coalition years it was a strikingly successful narrative. Osborne was not personally popular, but his economic story was clear and relentlessly consistent, and for a considerable time it proved effective in persuading voters that there was no alternative to spending cuts, and that they should support a government making the necessary tough choices. Cameron’s surprise majority at the 2015 election was in large part a product of that narrative coherence.

The UK since 2016: economic policy without a narrative

The post-2016 period shows us an alternative world, in which economic policy is made in the absence of a structuring narrative. A striking feature of recent British politics is the extent to which economic messaging has taken a back seat, even as the public continue to rank the economy amongst the most pressing problems facing the country. For slightly different reasons, each of the post-Cameron governments has found it impossible to assemble an analysis of the economy that is compatible with its policy commitments, so they have either chosen to say very little about the economy or have lurched between contradictory acts of rhetorical positioning.

The difficulties began with Brexit, which introduced a very large immovable object into the policy landscape, and one which could not be readily incorporated into an account of economic progress. Both the policy and the communications of the May and Johnson governments had to operate in the limited space which the fact of Brexit allowed – a constraint which is only now, and only slowly, beginning to relax its grip. May was preoccupied with Brexit to the exclusion of all domestic policy, including on the economy. Johnson’s 2019 majority left him in charge of two incompatible economic factions: on the one hand, free-trading Brexiteers who believed in minimal government intervention, and on the other hand, red wall Conservatives for whom a proactive ‘levelling up’ agenda would be necessary to hold on to their seats. There was no available narrative that could have reconciled these two camps, so the response was to make sporadic policy concessions to both sides and let the contradictions run. Narrative incoherence only deepened with the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, which forced the government into the kind of interventionism that past Labour governments could have only dreamed of, putting Johnson’s brand of casual libertarianism yet further at odds with itself.

Perhaps the only attempt at articulating an economic policy story in this period belongs to the ill-fated Truss-Kwarteng mini-budget. Truss did at least have things to say about the economy, but her narrative was all communication and very little coordination; the ideas were assembled at the level of buzzwords but very weakly connected to any serious analysis of the economy and its weaknesses in 2022. Its policy prescriptions were deregulation and tax cuts, harking back to the 1980s with what one Conservative former treasury minister memorably dubbed a ‘half-digested, two-dimensional version of Thatcherism’.3 Sunak and Hunt, in contrast, communicated as little as possible about the economy, and only when there is good news. As Chancellor, Hunt’s headline priority was been to bring down inflation, which in a context of internationally falling inflation was the policy equivalent of waving a train into the station. But an overarching story about the UK’s economic challenges, and the policies that might address them, has been nowhere in evidence for the last eight years.

Labour’s emerging narrative: a prescription at odds with the diagnosis

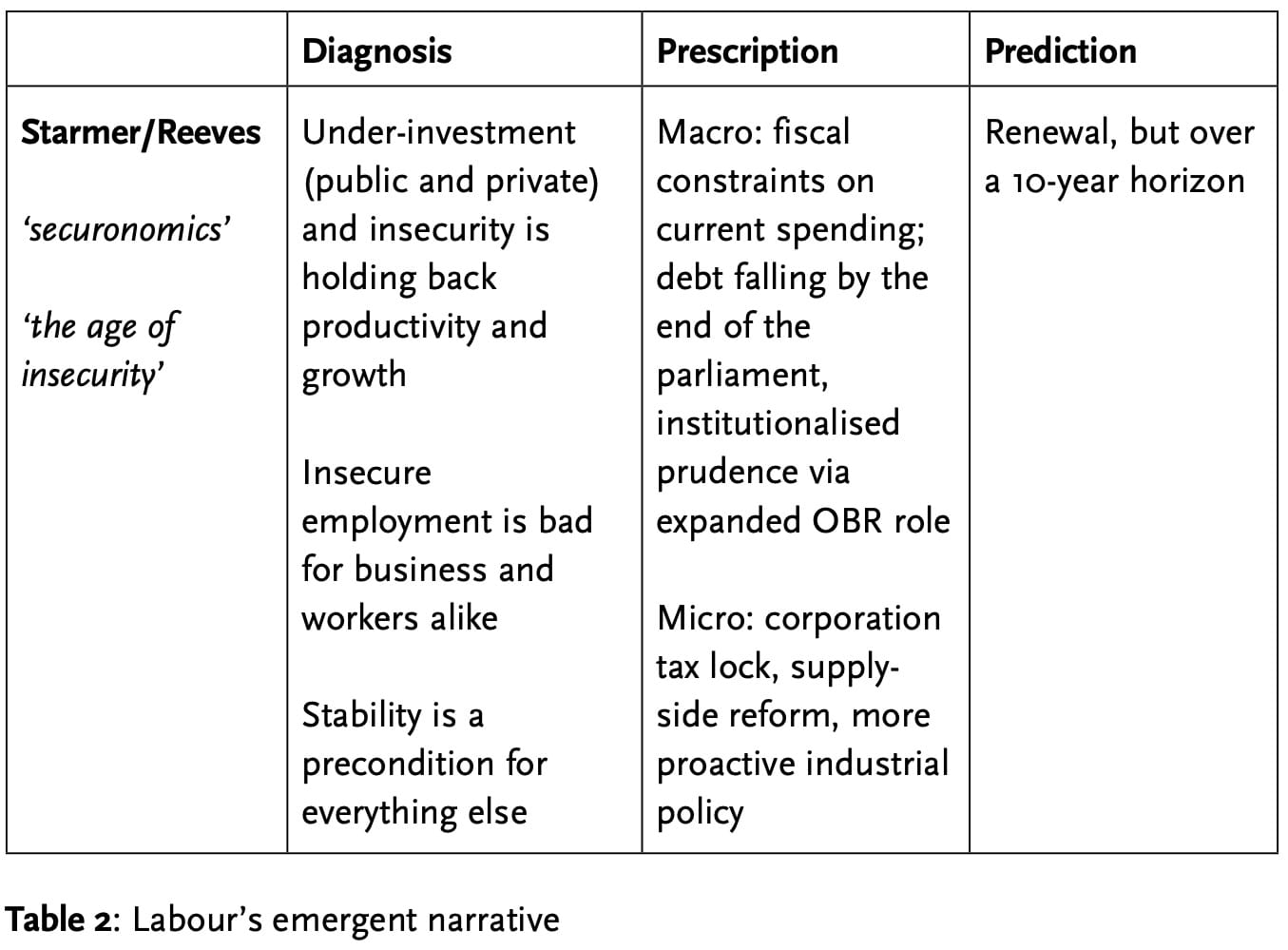

So what of the new Labour government? Before the election, the most fully elaborated statement of Labour’s thinking was Rachel Reeves’ Mais lecture in March, which devoted a good deal of space to the economic ideas of her predecessors, and their shortcomings. Out of that lecture a distinctive diagnosis had begun to emerge (Table 2). Reeves highlighted Britain’s chronically low investment rates, and the ‘historic negligence’ of the Conservatives’ failure to borrow for investment when interest rates were at rock bottom, arguing that it has left the UK in an ‘age of insecurity’. Her ‘securonomics’ tagline is a piece of jargon appealing only to policy nerds, but the underlying idea is promising: recognising that the precarity affecting many working people also affects the economy as a whole, and redefining economic prudence to include not just sound money but sound public services and infrastructure, because nobody will invest in a country that has resigned itself to visible decline. In significant ways, Reeves departed from New Labour thinking, from her critique of the ‘one-sided flexibility’ in our deregulated labour markets, to the need for a proactive industrial policy targeted at comparative advantage in sectors that can provide good jobs alongside output growth. There is an emergent narrative here, and it is reasonably clear-eyed on the perilous disrepair of the UK economy in 2024. So far, so good.

But a smart diagnosis is not much use if the link between analysis and policy is broken. Reeves is attempting to tread a fine line between making a plan for proactive, government-led renewal, and providing the usual assurances on competence and credibility, framed in narrowly conventional terms as a commitment to Labour’s stated fiscal rules. It is telling that it was only this fiscal self-binding that made it onto Starmer’s policy pledge card in May. Asked to pick just one economic message, it was fiscal restraint that rose to the top, making it clear that everything else Labour hope to do is conditional on the fiscal numbers staying within bounds. Current spending will be subject to a balanced-budget rule, alongside a commitment to see debt falling as a share of the economy within a five-year forecast horizon. If the economy is growing, that second rule will be met, but if projected output is weak, the second fiscal rule turns pro-cyclical, requiring spending cuts or tax increases to pay down debt in the absence of growth. This prioritisation of debt reduction then begins to cut across all the other problems Reeves identifies. For example, the Mais lecture highlighted ‘low levels of basic skills’ as a cause of weak productivity, but investment in skills – in the human infrastructure that might support future UK competitiveness – counts as current spending and falls foul of the first fiscal rule, thus making it harder to generate the growth that would allow the second rule to be met.

The unavoidable conclusion is that Labour’s policy prescriptions are at odds with their own economic diagnosis. Constraining current spending as tightly as these fiscal rules will require is not based on Reeves’ analysis of what the economy needs, but on the imported assumptions of two previous narratives. From Blair and Brown, Starmer’s Labour have retained the notion that stability can only be achieved by projecting fiscal prudence at all costs; from Cameron and Osborne, the idea that public debt is an ever-present threat to stability. As it stands, the only way Labour’s broad diagnosis and narrow prescriptions can be reconciled is if growth comes to the rescue. Delivering a higher rate of growth would allow debt to drop as a share of GDP without the need for further austerity or, if Labour are really lucky, even generate some new revenues. But this is a high-stakes gamble, both politically and economically. On the political side, it assumes that a country fourteen years into the consequences of austerity is prepared to wait another five or ten years before public services start to feel better again. And economically, it looks like pure wishful thinking to assume that in a context of secular stagnation and growing geopolitical instability, and in the absence of significant investment in the short term, growth is just around the corner. Starmer, it seems, is so concerned to show that he does not believe in a magic money tree that he must substitute a magic growth tree in its stead, potentially resigning the party to a first term spent defending a leftwing version of austerity.

There is one way growth might come back to the UK quickly enough to rescue Labour, and it’s the same way it always does: through a credit-fuelled property bubble that puts money in the pockets of homeowners and gets them spending again. Reeves’ plans to radically liberalise the planning system are framed as being pro-business, but everything about the UK’s recent economic history says that such stimulus tends to go first, and fastest, into residential property. Sweeping reforms of the planning system may clear the way for higher rates of housebuilding, and with inflation returning to trend, better mortgage deals will soon be available to support a new property boom and get the wheels of housing-led growth turning again. But if indeed the UK turns to its familiar housing- and credit-based growth model,4 the consequences for inequality, both intra- and inter-generational, are not hard to predict. These are the trade-offs that the coordinators of Labour’s narrative must confront: are they willing to resort to the quick stimulus of a property boom in hopes of driving investment down more productive channels later? And if so, how will that reorientation towards productive industries be achieved? Or would they rather find fiscal space to try to stimulate growth in other parts of the economy, sooner rather than later?

The years since 2016 have illustrated the dangers of making economic policy without a narrative. When economic choices are driven, not by serious analysis, but by working around policy fixed points, all hope of a serious economic strategy is gone. To govern is to choose, but to choose without any anchoring principles, besides fear of appearing imprudent, is not to choose but to continually react within a shrinking field of options. Labour are on their way to a serious diagnosis of the problem, but cannot yet bring themselves to prescribe the investment it implies. No effective narrative can sustain such contradictions for long.

To be clear: while every government needs an economic narrative, this is not to imply that they can narrate the conditions any way they want. The Truss debacle is ample evidence that economic policy takes place in a materially interconnected world in which governments must tread carefully, and facts matter. But the only way to make economic policy coherent, and to give it a chance of making meaningful change in the intended direction, is to assemble a narrative that begins with the economy and then reckons with policy choices and constraints, not the other way around. The alternative is another five years of incoherence and unintended consequences.

There is perhaps a cautionary note in the other direction. Narratives that coordinate at the beginning, but then treat their analysis as a settled fact to be repeated forever, risk institutionalising the errors in their thinking. The New Labour years are a prime example of a narrative devised for one set of economic conditions which became increasingly rigid, and resistant to recognising contraindications in the real economy. Narratives that empower policy at the beginning of a political cycle can become major constraints if the world changes and they do not, so governments must build in a challenge function to their policymaking processes. But now, at the beginning of their political project, Starmer and Reeves’ key test is whether they yet have a narrative that makes coherent sense both for its context, and in its own terms. If the fiscal rules do not allow them the space to connect diagnosis to prescription, they must begin steering towards a framework that can. Narrating their vision of the good economy is part of the work of opening up that policy space.

Kate Alexander-Shaw is a Research Officer in the European Institute at the London School of Economics. Her work spans British politics, comparative political economy and the recent politics of crisis in the EU. She has previously been a policy analyst at the Treasury and the Greater London Authority. She is the author of the chapter ‘An Economy for All?’ in the new textbook An Introduction to UK Politics (edited by Joanie Willett and Arianna Giovannini), available from SAGE.

Notes

- Schmidt, Vivien, 2011. ‘Reconciling Ideas and Institutions through Discursive Institutionalism’. in Béland & Cox (eds.) Ideas and Politics in Social Science Research. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Stone, Deborah, 1989, ‘Causal Stories and the Formation of Policy Agendas.’ Political Science Quarterly 104, 2, pp281-300

- Financial Times, ‘Letter: Truss has little grasp of UK’s structural problems’ Letter from Phillip Oppenheim, Conservative Exchequer Secretary to the Treasury (1996-97), 30 September 2022. Online at https://www.ft.com/ content/9d358603-3633-4eec-8912-de55fe07d930

- See Reisenbichler, A. and Wiedemann, A, 2022, ‘Credit-Driven and ConsumptionLed Growth Models in the United States and United Kingdom’ in Baccaro, L., Blyth, M. and Pontusson, J. (eds.) Diminishing Returns: The New Politics of Growth and Stagnation, Oxford: OUP