David Lawrence

A customs union won’t fix Labour’s growth woes

The Government is, we are told, considering crossing its own red lines and rejoining the EU Customs Union. Indeed, according to one Cabinet source, this is “the only idea around” on growth.

Aside from being an indictment of the quality of ideas around, this says a lot about Britain’s failure to reckon with its fundamental economic challenge: a lack of dynamism. Brexit didn’t cause our economic stagnation, but it did create the belief that our stagnation can be blamed on it.

Westminster’s obsession with Brexit is both touchingly optimistic–if we could just fix this one thing, we’d be rich!–and distractingly inhibiting, as it implies that no economic reform is possible or worth considering unless and until we address what is still (inexplicably) referred to as ‘the elephant in the room’.

Brexit has undoubtedly been bad for Britain’s economy, probably to the tune of about 4% of annual GDP by 2035. From car manufacturers in Coventry to musicians in York, from shoppers in London to potters in Stoke, Brexit has hit exporters and inflated prices, sapped confidence and drained investment.

But if the key to growth were removing customs checks, or even Single Market membership, countries like Germany, France and Italy would have seen very different growth rates from Britain since 2016. In fact, they haven’t.

When it comes to economic growth (or lack of it), Britain is recognisably European. Like France, Germany and Italy, our GDP per capita is more or less the same as it was 10, 15 or even 20 years ago. Since the financial crisis, productivity has remained stagnant across the board in pretty much all Western European countries.

Meanwhile, if Britain had grown at the same rate as the US since 2007, each household would be 12% better off – for a household on £50,000 income, that’s £6000 extra each year. It’s about 3x larger than the projected Brexit impact on productivity.

Brexit gives us a scapegoat, an easy answer, an excuse not to dig deeper and make more fundamental choices to pursue growth. Even the Prime Minister, who has hitherto avoided the B-word, now says that Brexit was “utterly reckless”, and that we need to “confront the reality” that leaving the EU was bad for growth.

It is a view that has long been held by our political leaders, even when they avoided talking about it, as well as a majority of the general public, including many Brexiters themselves. The problem is that it isn’t really true.

Instead of focusing on Brexit, we should ask ourselves why the US has managed to grow at a rapid pace since the financial crisis, despite isolationist trade policies and populist politics. That is the question to which Starmer and Reeves should devote their attention.

Sceptics argue that we have little to learn from American growth, because the US exists in its own reality. A country like Britain can’t just decide to have the world’s reserve currency, become the largest military power, or use Trumpian tariffs to force concessions from tributaries. These factors are real, but hardly new: they do not explain why Western Europe and the US grew at similar rates between 1945 and 2007, and have since diverged.

There are many reasons for this divergence, but if it had to be summed up in a word, the most obvious difference between American and European economies today is a difference in dynamism.

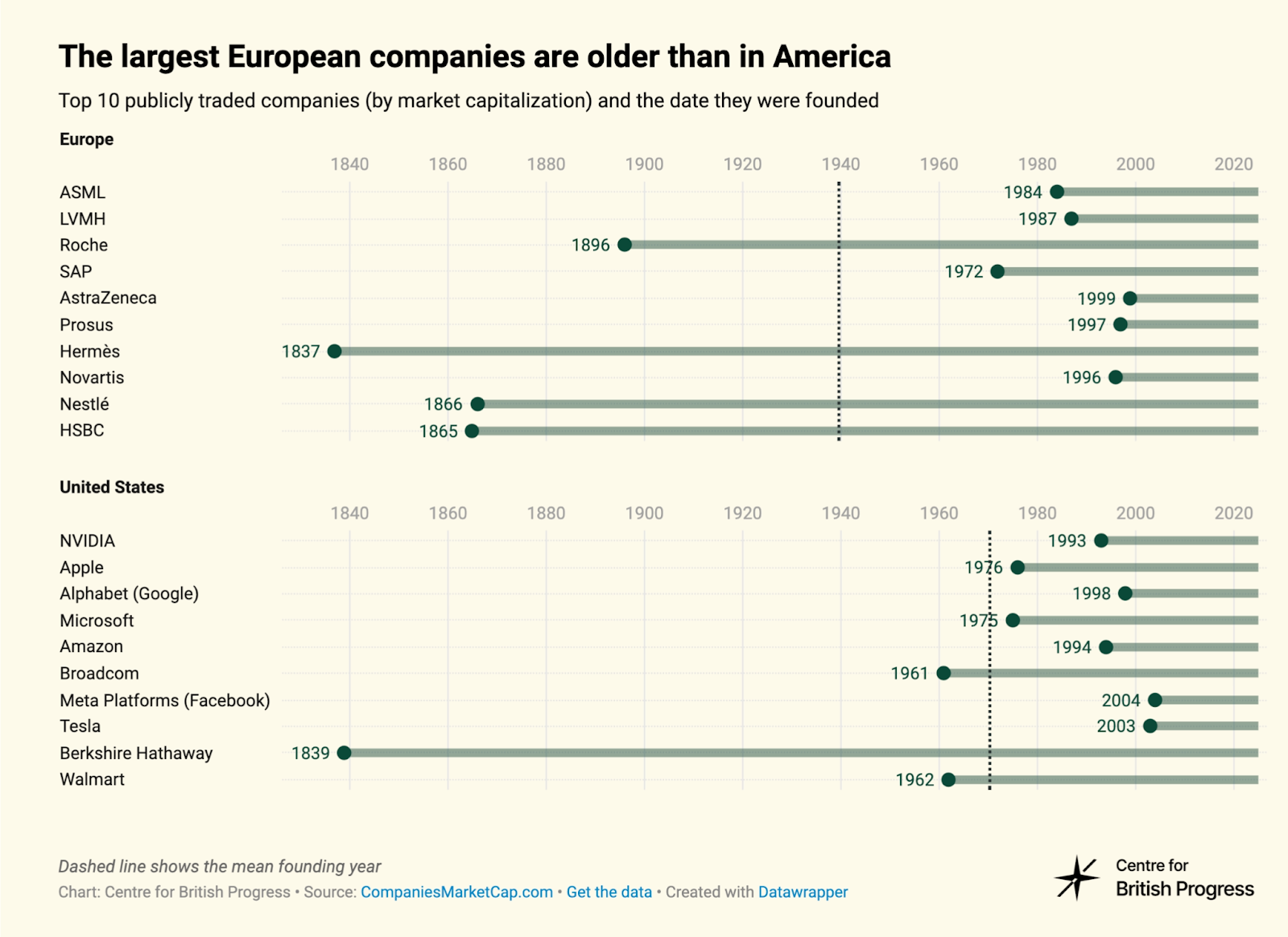

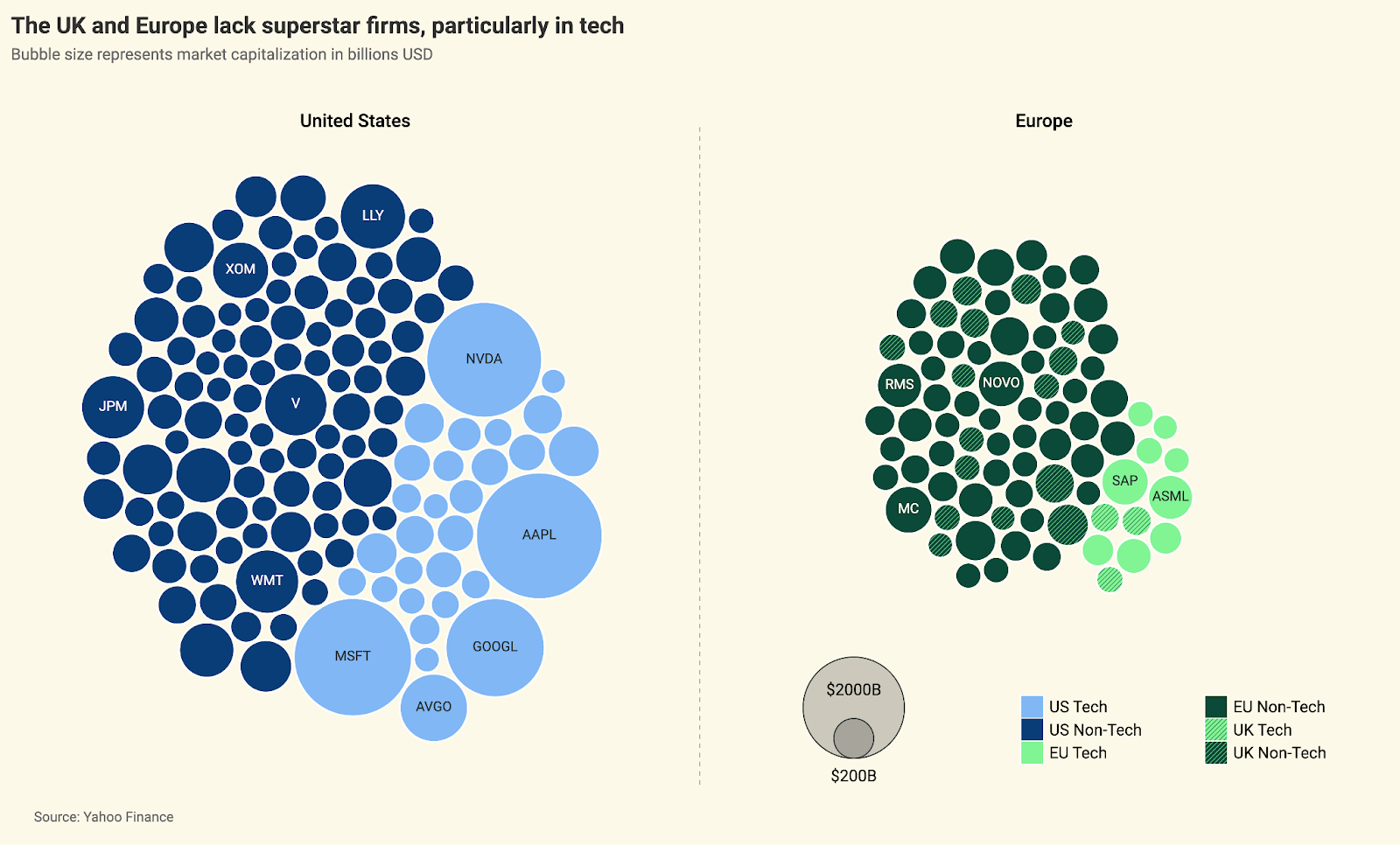

Dynamic economies are adaptive and opportunistic. A tell-tale sign of a dynamic market is one where new companies can quickly take on and beat established incumbents. Of the 10 largest companies in the US, eight specialise in technologies that didn’t exist 20 years ago, 6 did not exist before 1991, and two (Meta and Tesla) were founded since the millennium. Corporate success in the US today looks very different compared to 20 years ago. That’s a sign of dynamism. As the economist Brian Albrecht argues, the US economy has seen an increase in market share for the most productive companies. It is not clear that the same has happened in Europe.

Meanwhile, Europe’s top ten features more companies from the 19th Century (3 firms) than the 21st (none at all), and only two are in digital technology. Britain’s top 10 features just one tech company, ARM, owned by Japan’s SoftBank. European wealth tends to be held by the same families and companies that held it 100, or even 200, years ago: aristocratic landowners, financiers, owners of old and established companies.

Crucially, dynamism is not the same as innovation. Britain, like many European countries, has no shortage of entrepreneurs and inventors, scientists and creators. The challenge is continually re-allocating talent and capital towards evermore productive uses, in effect turning ideas into profitable companies that can take on incumbents and scale. For this, market structure, regulation and underlying infrastructure are more important than ingenuity and skills.

Britain, like much of Europe, struggles with these fundamentals. The most prominent of these is a failure to build. We do not build enough housing, particularly in productive cities, and especially in London. This means workers can’t afford to move to good jobs, and wages are inflated to cover high rents, increasing cost and reducing business investment. The area between London, Oxford and Cambridge should be Europe’s Silicon Valley or Shenzhen. Instead, sheep graze on the land around Heathrow, and Oxford and Cambridge have not been connected by rail since 1967.

Housing is the most obvious bottleneck. But it is difficult to build anything. Britain has some of the highest electricity costs in the world, in part due to our failure to build transmission infrastructure and baseload nuclear power. We have not built a reservoir since 1992, or a runway since 2001, or high speed rail since 2007. This is as much a function of a broken planning system as broken regulatory frameworks that promote asset-sweating over investment.

Physical infrastructure is important for dynamism because it effectively levels the playing field. Productive firms cannot take on established incumbents if they face prohibitive costs to expansion. Good firms buy and sell from other good firms, so supply-side barriers reduce demand for other companies that could otherwise scale. The net effect is dampened investment and firms that would rather scale in the US–or not at all.

Simplistic calls to rejoin the customs union, or even the EU entirely, also overlook that Europe is going through its own period of self-reflection. Mario Draghi, former head of the ECB, has called for Europe to overcome regulatory hurdles to embrace dynamism. He proposed establishing an EU-wide legal framework (the "28th regime") to simplify and standardize the rules for businesses, especially those in digital and deep technologies. Yet progress has been slow. The answer cannot simply be to turn the clock back and rejoin an institution that is now clearly facing its own existential moment. Europe and the UK must both take their economic stagnation seriously, rather than simply teaming up in decline.

Britain’s economy is European, for better and for worse. Joining the Customs Union would most likely be good for growth. But if we think it will save us from economic stagnation, we are suffering from a very British form of exceptionalism. Whether we’re in or out, Britain must rediscover its dynamism.

David Lawrence is co-founder of the Centre for British Progress.