Jimena Valdez

Lessons for economic growth from Pedro Sánchez’s Spain

In a recent issue of Renewal David Cesar Heymann wrote about one of the most successful social democratic governments in Europe: that of Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE) leader Pedro Sánchez (2018–). The current PSOE government is compelling not only for the remarkable trajectory of its leader—from party outcast to repeatedly victorious prime minister—but also for its parallels with Labour in the UK. Both came to power on the back of disillusionment with right-wing governments, and both have faced enormous economic difficulties in office.

Heymann argues that three factors explain PSOE's success: the party established a clear political cleavage with the right; delivered material improvements for its base; and projected an image of audacity. The article concludes by outlining lessons for Keir Starmer's government: that technocracy is not enough and government must be seen to deliver; that voters reward audacity and boldness; and that leaders should not cling to campaign pledges at the cost of effectiveness.

I return to Spain in this post not only because Sánchez met Starmer in London recently, but also to expand on the lessons that the country offers for the Labour government. These concern both the lessons for political leadership that Heymann points to, but also the Sánchez government’s strategies for generating economic growth.

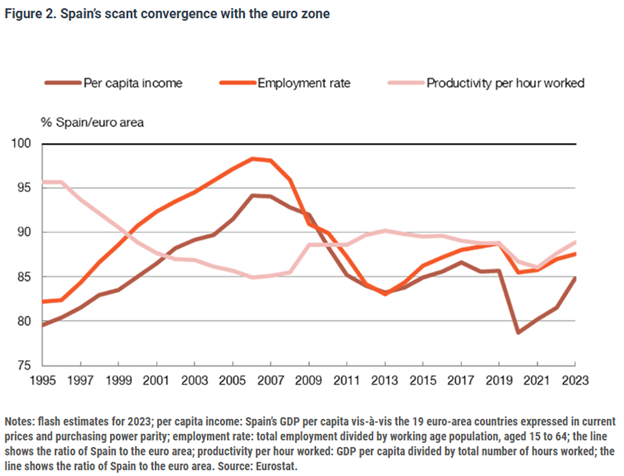

While the UK is richer than Spain, there are striking parallels in their economic trajectories. Spain's income per capita was converging toward EU levels before the 2009 financial crisis, but that process has since stalled and has not resumed.

Source: https://www.realinstitutoelcano.org/en/commentaries/economy-doing-better-but-no-room-for-complacency/.

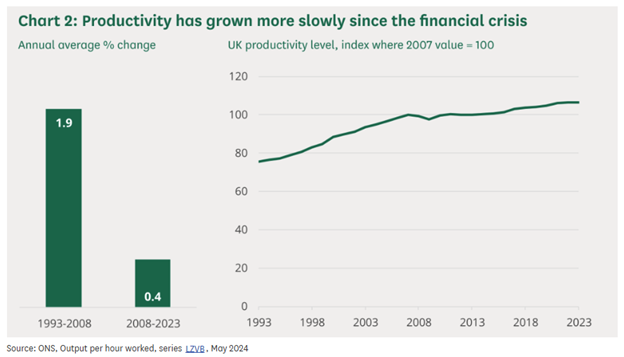

The UK economy has similarly disappointed since the crisis.

Source: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/low-growth-the-economys-biggest-challenge/.

As shown in these graphs, Spain's productivity has consistently lagged 10-15% below the eurozone average since 2008. The UK also has a productivity problem.

Today Spain is the EU's fastest-growing economy. It grew 3.2% in 2024 and is projected to grow another 2.6% in 2025— this compares starkly with Eurozone GDP growth below 1% in 2024, with similar forecasts for 2025. Meanwhile unemployment, long one of Spain's most persistent problems, has dropped to 11%—its lowest level since December 2007, just before the crisis began.

Spain thus offers two additional lessons for the Starmer government about how to pursue economic growth creatively and pragmatically, and about the need to turn this growth into rising living standards.

Lesson One: Creative and Pragmatic Growth

Spain's growth defies the usual Eurozone policy recommendations of lowering labour costs to boost international competitiveness and deliver export-led growth. Spain's response to the 2009 financial crisis, like that of its neighbours, combined austerity with structural reforms—including, crucially, labour market reform that made dismissals easier and cheaper. People lost jobs and were rehired at lower wages. But despite documented falls in labour costs, the pivot to export-led growth never materialised and is not expected now. Instead, Spain’s current exceptionally high growth rates have stemmed from tourism, immigration, and domestic demand.

1.1 Tourism as Strategic Growth

Tourism has long been key for Spain. Yet under PSOE, it has shifted in important ways. Tourism is becoming less seasonal, is spread more evenly across regions, and it is shifting away from sun and beach holidays and towards cultural, nature-based and active tourism. This sector alone has improved Spain's current account balance, even as goods exports remain sluggish.

What is the lesson for the UK? Growth can come from unexpected places and can be shaped strategically over time. Higher education is a sector with strong potential for growth. The UK could build upon its status as a global leader in higher education, benefiting economically from international students no longer able or willing to study in the United States. While the number of students coming to study in the UK has been used to raise alarm about high levels of total immigration, this is a very different and specific phenomenon. The vast majority of international students (80 per cent) leave within five years of arrival, and those that stay need to transition into another type of (work) visa to be able to stay for a longer period of time. Increased numbers of international students would help fund universities—a sector in crisis in the UK—boost consumption and bring skills to the country. Thus, international student recruitment should be shaped strategically to align with other government goals, such as AI investment and development.

Despite these material advantages, the UK has tightened conditions for international students—from increased fees to restrictions on dependents—resulting in declining numbers. This brings me to the next point.

1.2 Immigration as Growth Driver

The second key factor in Spain's exceptional growth is immigration. Between July 2021 and July 2024, Spain’s immigrant population grew by over 1.2 million people. Today, immigrants constitute 18% of the population in Spain. Morocco is the main origin country followed by Colombia, though more generally Latin American migrants constitute almost 50% of the total (before Europe and Africa). Between late 2019-2014, almost 80% of new positions in the labour market were occupied by immigrants. These provided much-needed labour (especially in sectors struggling to attract Spanish-born workers) and fuelled private consumption. Indeed, between 2021 and 2023, one-quarter of increased household consumption came from immigrant-led households.

In this context, Pedro Sánchez is one of the few European leaders arguing for legal immigration, reframing it not only as a moral duty but as an economic necessity to sustain and grow the Spanish welfare state. The Bank of Spain has claimed that to keep the dependency rate constant (at 26%), Spain needs immigrant population to increase in 24 million to a total of 37. In line with this, Sánchez has stated that “Spain must choose between being an open and prosperous country, or a closed and poor one.”

The UK, with its specialisation in international services, health and social care sectors reliant on migrant labour, and rapidly growing dependency ratio, can learn from Spain's economic gains from immigration. The Labour government should develop a rational, strategic approach to immigration beyond merely reacting to far-right agitation.

1.3 Domestic Demand and Public Investment

The third growth driver is domestic demand—mainly investment and private and public consumption. Government spending on education, healthcare, and culture has played an important role in Spain’s economic recovery and is expected to continue. In 2025, growth will likely be driven again by private consumption (supported by the strong labour market), investment, and Next Generation EU fund deployment.

The Labour government, by contrast, has inherited tight borrowing rules that prevent public spending. Fiscal discipline is familiar to social democratic governments prone to appeasing markets, but it is hardly a recipe for economic success. The fact that Sánchez is the only social democratic prime minister in a large EU country might be testament to that. Governing for growth, in the Spanish case, means spending.

Lesson 2: From Growth to Living Standards

This leads to the second lesson: economic growth must be transformed into improved living standards.

Here Spain offers both achievements and warnings. Despite exceptional growth rates, ordinary Spaniards have yet to feel improvement in their pockets. GDP is growing, but due to population growth GDP per capita has grown much more slowly. Employment is at a record high, but because the working population is also larger unemployment has fallen more gradually. Despite recent wage increases, real median earnings remain below pre-crisis levels. Inequality remains high—about the same as before 2008. Inflation has also taken its toll: per capita private consumption remains below pre-COVID levels. These limitations on Spain’s economic recovery do not even include the housing crisis, arguably the country's most urgent challenge.

Unsurprisingly, many Spaniards feel things have not really improved—a feeling that is shared by UK citizens, and poses a significant risk for the Labour government

Labour was elected promising change and delivery: improving the NHS and other public services, increasing economic growth, and reducing the cost of living. Yet more than a year in, it remains unclear whether this has happened—or even whether the government has taken meaningful action to deliver on its promises. Instead, we see a government squeezed on all fronts, most importantly by its own tight fiscal rules. This failure to deliver appears to underlie historically low government popularity and high defection rates among Labour voters. The perception that the government has broken its promises, combined with unrelenting cost of living pressures, drives voters to parties on both left and right.

What should the government do? Spain shows that economic growth is necessary but insufficient. UK citizens want improved public services and living conditions. This will not happen without additional investment. Sustained growth—the kind that actually impacts living conditions—requires a state willing to invest. It comes from serious R&D commitments, from strategies that harness the benefits of immigration, and from public spending.

Jimena Valdez is Lecturer in Politics at King’s College London. She researches business and labor politics.