Colin Hay

The ‘New Orleans effect’: The future of the welfare state as collective insurance against uninsurable risk

Feb 14, 2026

Editors’ note

Analysis of the welfare state tends to assume that welfare-related institutions and practices develop along a well-trodden path, whereby shocks from outside may interrupt, but not alter, a given developmental trajectory. This is partly because such shocks are relatively rare. Welfare states protect us, collectively, against insurable and knowable risks, essentially by decommodifying them: we pay for welfare collectively through the tax system, not individually through the market. Countries obviously differ greatly in what (and how) they choose to decommodify, but the key parameters of welfare capitalism are assumed to be unchanging. Yet as we enter a new age of human-generated environmental catastrophe, it is not difficult to see that exogenous shocks are now increasingly likely – nor where they are most likely to come from. Welfare states will increasingly be asked to insure us against uninsurable risks associated with the climate crisis. It is not clear that they will be able to do so, nor that we even have the analytical tools necessary to understand how welfare provision is now developing. In a major, original contribution to scholarship on the welfare state, this article draws upon and critiques academic literatures around welfare and decommodification, as well as challenging the institutionalist assumptions that underpin our understanding of welfare capitalism and its international varieties. In doing so, it also delivers a stark warning to policy-makers – and all of us – about the future of the welfare state. Readers are also encouraged to visit the Renewal blog over the coming weeks, where several leading scholars (including Mark Blyth, Waltraud Schelkle, Daniel Bailey, and Nick O’Donovan) will be responding to this article’s argument.

* * *

We are entering, if we have not have already entered, a new phase in the life-course of the welfare state. Set in any kind of comparative historical context it is likely to look very distinctive. For it will see the strange and potentially alarming co-presence of three conditions:

- Welfare state spending rising to previously unprecedented levels (whether expressed as a percentage of GDP or, as perhaps it should be, on a per capita basis)

- Expenditure rising, but still failing ever more systematically to protect and insure citizens against the risks (both individual and collective) they face

- An ever-greater proportion of such spending being debt-fi nanced in an age of ostensible austerity.

The likely consequence of the third condition is a new fiscal crisis of the welfare state and pervasive debt default.

This, on the face of it, seems paradoxical. How is it that welfare spending might swell to previously unprecedented levels yet fail to meet the needs of citizens? And how is it possible to imagine an ever-greater mountain of public debt capable of precipitating a fiscal crisis of the state and public debt default in an age of institutionalised and normalised austerity? In what follows I will seek to unpick and resolve the paradoxical nexus, to explain how it is that we now find ourselves in such a situation and to explore at least some of the implications.

Crucial to all of this – and the key to unlock the puzzle – is the uninsurable risk associated with what I will call environmental catastrophism. The new phase in the life-course and developmental trajectory of the welfare state to which I refer is, then, in fact an epiphenomenon of a more general condition.

That condition is the dawning of a new stage in what is usually referred to as ‘the Anthropocene’. Whilst the term has been much debated and contested, here I take it to refer simply to a period, akin to a geological epoch, in which the climate of the planet becomes profoundly shaped by and thereby contingent upon the consequences of human agency.1 Within this rather longer span of geo-ecological time, I argue, we are entering (or have perhaps already entered) a new stage – a stage in which both the probability and the severity of environmentally catastrophic events rise exponentially, and once low-probability events become the new normal. We are entering, in short, an age of anthropocenic environmental catastrophism.

This, I contend, will have profound consequences, amongst other things, for the form, functioning and financing of the welfare state.2It is with those consequences that this article is principally concerned.

If such a diagnosis is correct then it is no less clear that we are not prepared for such an eventuality and that the existing literature on welfare state development does not prepare us well for this moment – nor, arguably, are the analytic resources it provides particularly helpful in making sense of it. My aim in what follows is to begin to think about what we might need to do to gain greater analytic traction on the problem and to consider what taking such a diagnosis seriously might imply.

Yet it would be wrong to suggest that there is as yet no literature on this topic. Indeed my concern in this article parallels closely that of Andreas Duit and his co-authors with what they call ‘the evolution of contemporary states once environmental issues become an important preoccupation of government’.3 The precise formulation of the phrase is interesting, not least as it comes from one of the rare attempts to consider the interdependence of political ecological and political economic factors in the forging of current and future welfare state trajectories.4 For it implies that environmental issues were not considered ‘an important preoccupation of government’ even as recently as 2016. That seems to me credible; but, crucially, it is perhaps no longer the case. When it comes to the dawning of environmental catastrophism, seven years – notably the last seven years – turn out to be a long time. It is rather more credible today than it was when these words were written that it would only be through the advent of catastrophism that the immediacy and importance of such issues would be forced upon the state – that the self-imposed impotence of the state’s response to date would be overtaken by events, as it were.5 We may or may not have reached that point. But even on the most optimistic of readings, it now seems very close at hand.

I will assume, for now, and in what follows, only that we are on the verge of a potentially epoch-shaping moment in and though which our anthropocenic interdependence becomes demonstrably catastrophic in its consequences and in ways likely to precipitate significant state action. The majority of existing climate models now point clearly in that direction.

My argument proceeds in three stages. In the first, I explore the challenge to the existing literature implicit in the previous paragraphs. When it imagines the future of the welfare state, the existing institutionalist political economy of welfare capitalism projects the path-dependent reproduction of welfare typicity in the absence of (unanticipated and untheorised) ‘exogenous shocks’. Yet as we enter a new age of anthropocenic environmental catastrophism, it is not difficult to see that such shocks are likely, nor where they are most likely to come from. They are no longer unanticipated and there is no longer an excuse for leaving them untheorised. It is time to endogenise them.

In the second stage, and in the light of this, I propose that we revisit our definition of the welfare state, rejecting, or at least supplementing, Gøsta Esping-Andersen’s classic focus on decommodification, with a broader conception of the welfare state as the insurance of citizens against insurable and, above all, uninsurable risk.6

In the third, I explore the implications of this for an understanding of the future of the welfare state in an age of anthropocenic environmental catastrophism. I show how such a conception leads us to anticipate a new fiscal crisis of the welfare state, associated with the cost of insuring citizens against risks for which there is no market premium in an age when those risks become ever more prevalent and ever more menacing.

Towards a political ecology of the welfare state

Like much in academic political economy, the existing comparative literature on welfare system dynamics is institutionalist in analytical structure. It characterises institutional trajectories as path-dependent, if not entirely incremental. As such, it tends to assume that existing welfare systems are in a default condition of dynamic equilibrium unless disturbed by ‘exogenous shocks’. Such shocks, by virtue of being construed as exogenous, remain untheorised within such accounts. ‘Exogenous’, in other words, means external to the theory.

There is nothing inherently problematic about such a conception. It is neat, it is parsimonious, and it has served us very well. As it happens, I have great intellectual sympathy for it.7 But it is limited. Indeed, in a sense, it is quite consciously self-limiting. For it externalises (and thereby places beyond the account it offers) what it nonetheless acknowledges to be potentially significant drivers of welfare system dynamics (those famous ‘exogenous shocks’). It prepares us well for a world in which what happened yesterday is the best predictor of what will happen tomorrow; but it prepares us hardly at all for a world of seismic shifts and radical uncertainty. It comforts itself, presumably, with the thought (a now perhaps comforting delusion) that, most of the time at least, we do not live in such a world.

The self-imposed limits of such an analytic strategy are nowhere more cruelly exposed than when it comes to the question of the interdependence of the political economy and political ecology of the welfare state, above all today.8 By externalising the latter, that interdependence is essentially denied, at least theoretically. For whilst most institutionalist political economists of the welfare state would surely acknowledge (if asked) that such an interdependence exists, the analytic assumptions upon which their theoretical account of welfare system dynamics is predicated precludes any theorised account of it. It is, in effect, dismissed as random (if potentially disruptive) noise emanating from beyond the concert hall. Put slightly differently, in any situation in which it were acknowledged that welfare system dynamics were likely to be driven by political ecological factors, the political economy of the welfare state literature would have little or nothing to offer, at least until it were established that such an exogenous shock were in play.

That is precisely the situation, I contend, in which we find ourselves today. It suggests that the world imagined by the existing institutionalist political economy of the welfare state is rather different than that which might be imagined by a putative political economy more amenable to acknowledging theoretically the interdependence of political ecological and political economic dynamics.

This is not perhaps the place to elaborate on what such an alternative might look like theoretically – certainly in any detail. But it is not difficult to see how the two approaches might develop wildly divergent views of credible welfare futures.

Within the conceptual universe of the former conventionally institutionalist approach, welfare states (or capitalisms) come in varieties (typically, three, four or five varieties), and, in some variants at least, are now associated with a perhaps greater diversity of growth models.9 Within-type variance – at any given point in time and over time – is limited (though, typically, greater where a link to growth models is made explicit). Even if paths can converge or diverge, between-case variance is patterned over time and within-case variance is path-dependent. Typicity endures, paths are continuous, their evolution over time incremental and path transcendence is both exceptional and, invariably, attributable to the presence of a more or less commonly experienced exogenous shock.

The expectations of such an approach with respect to the future are clear. Since the institutional architectures constitutive of welfare systems are slow moving, we should anticipate, all things being equal (and the ‘exogenous shock’ clause notwithstanding), continuity and/or path-dependent gradualism.

Within the alternative, even if as yet somewhat putative, ‘political and ecological economy’ approach, the welfare of citizens is contingent upon the broader environment (literal and figurative) in which those citizens find themselves. So, too, by implication, is the policy challenge faced by a state responsible for meeting in whole or in part the welfare needs of those citizens. If that environment is both non-anthropocenic and benign, then welfare trajectories may well be anticipated to be largely determined by institutional factors and, correspondingly, path-dependent. In short, under such conditions, the existing political economy of the welfare state is likely to prove a reliable guide. Note also that this remains the case whether the environment in question is eco-systemic, political or economic (the sole significant difference being that in the latter two cases, the relevant environment is necessarily anthropocenic).10

Crucially, however, if the same environment is neither non-anthropocenic nor benign – and, above all, if it is non-benign because it is no longer non-anthropocenic – then welfare trajectories are likely to be disrupted by environmental contingencies. Those contingencies are, in turn, unlikely to present themselves in ways that respect pre-existing institutional traits and characteristics such as welfare regime typicity in any of its multiple guises.11 In short, path dependence is no longer guaranteed. Differential exposure to environmental contingencies is, in short, sufficient to shatter the assumptions of a narrowly institutionalist political economy of the welfare state.

In effect, what this second perspective does is to re-endogenise the exogenous shock.12 It does so by suggesting, at least implicitly, that every external shock exposes an endogenous frailty. This is almost akin to an institutionalist third law of Newtonian mechanics: for every exogenous shock there is an equal and opposite endogenous frailty. Rather than exogenise the shock, we should endogenise the frailty that it exposes. As such, all credible endogenous frailties need to be found a place within a political economy of the welfare state fit for the times in which we acknowledge ourselves to be living.

In what follows, I seek to explore – in a necessarily preliminary and provisional way – the implications of endogenising the succession of exogenous shocks that an age of ecological catastrophism is likely to impose on welfare system trajectories. But in order to do that, we need first to return to the definition of the welfare state itself.

From welfare as decommodification to welfare as insurance against collective risk

The conventional institutionalist political economy of the welfare state from which this reflection departs is more closely associated with the early 1990s work of Gøsta Esping-Andersen than with any other single author. And, perhaps partly as a consequence, it tends to draw its conception of the welfare state largely from him.

The welfare state, couched in his terms, is decommodifying. It takes what would otherwise be supplied to citizens in and through market mechanisms as commodities and provides such goods to them as a matter of right or entitlement. As Esping-Andersen himself puts it, ‘decommodification occurs when a service is rendered as a matter of right, and when a person can maintain a livelihood without reliance on the market’.13 The former is a means to the latte r.

Like the comparative institutionalist political economy of the welfare state to which it gives rise, and on which, to a significant extent, it is predicated, EspingAndersen’s conceptualisation of welfare as decommodification is neat, parsimonious and fit for the purpose for which it was intended. It provides, above all, an excellent basis for the topologising of European welfare system diversity in the post-war period (difficulties associated with its empirical operationalisation notwithstanding). But it, too, has its limits – above all in a context (that of today) rather different to that in which it was developed.

To see those limits, it is useful to return to an older, perhaps even more venerable and, indeed, pre-institutionalist understanding of the welfare state, one that, in a sense, underpins Esping-Andersen’s own concept of decommodification. That understanding conceives of welfare as social or collective insurance and the welfare state as that complex of policies, agencies and institutions charged with the collective insurance of the population.14 Viewed in such terms, the welfare state provides its citizens with insurance against a combination of risks and, indeed, risk types (something we will need to return to presently).

The welfare state – a state committed, whether contractually or more implicitly, to ensure the welfare of its citizens – becomes, in effect, a guarantor that citizens are appropriately insured against known (and, indeed, unknown) risks. In order to achieve this it becomes both a public and a private good provider of last resort. It is a public good provider of last resort in the sense that, in a market society it is the state, and only the state, that can intervene to ensure the public good when the market fails; and it is a private good provider of last resort in the sense that it is the state, and only the state, that can provide private goods to those who cannot afford the market-determined price for such goods.

It is easy to see how this leads Esping-Andersen to see welfare as decommodification, and the welfare state as decommodifying. For by insuring citizens against a combination of individual and collective risks it renders private goods public (by providing collective insurance against unevenly distributed risks). At the same time it removes entire categories of risk from the private insurance market. For if the state insures all of its citizens against the risk of unemployment, there is no need for citizens to insure themselves privately against such a risk.

As Ian Gough and James Meadowcroft put it, the welfare state thus understood ensures ‘the public management of social risks, usually idiosyncratic risks [which are] unpredictable at the individual level but collectively predictable, such as ill-health or unemployment’.15 To meet such risks, the welfare state transfers goods and services from the realm of market determination to that of political guardianship (by rendering them as social rights and enshrining them in some kind of citizenship contract). This typically covers, at least in the OECD world, insurance (however inadequate and partial) against old age, disability, sickness and unemployment, as well as a variety of other life contingencies.

The ‘welfare provision as decommodification’ formulation is helpful here. But it is not entirely unproblematic, at least in terms of one of its implicit assumptions. It needs revising in this respect before we can proceed.

Esping-Andersen, and most of those who have followed in his path, assume that the bundle of private goods that the welfare state renders collective and public was, before such a transformation, previously offered to the same citizens (or at least to their progenitors) in the market as private goods. It assumes, in short, that such goods had a prior existence as commodities before they were de-commodified.

That is fine for what are typically referred to as insurable risks: risks for which there is a market-determined insurance premium (whether one can afford to pay it or not). But not all risks are of that kind. At least as significant – and, I will argue, in an age of environmental catastrophism, of ever-growing significance – are uninsurable risks (those typically referred to in insurance policies as ‘acts of God’). For such risks, there is of course no market-determined insurance premium.

Crucial for the analysis to come is that the state has always insured its citizens against a combination of both insurable and uninsurable risks. But the existing literature has tended to focus almost exclusively on the former at the expense of the latter. It is not difficult to understand why; but nor is it difficult to see that, today, this is an error. For the welfare state’s insurance of citizens against uninsurable risk is often only implicit. It is implicit precisely because – as noted above – the welfare state is, in such matters, a public good provider not of the first resort but of the last resort, especially in conditions of market failure. And, it is often only in the last resort that it becomes clear what the state would do (and, in a sense, always would have done) in the final analysis – in the last resort. That the state would insure you against uninsurable risk only becomes clear when that risk becomes manifest as actual harm. That is what ‘the last resort’ means.

When the banks of the river burst and flood the village, when the landslide destroys the properties below, when the run on the bank means that no cash is available from the cashpoint machine, the state, it turns out, steps in. In so doing, it insures citizens (and other stakeholders too) against uninsurable as well as uninsured risks. That, I want to suggest, is welfare – and, if the (implicitly or actually) insured party is a citizen, it is public welfare, that is, the welfare state.

The implication of this is that the welfare state is not, and never really has been, just about decommodification – taking things that were (or would otherwise be) commodities and turning them into public goods. It is also about taking responsibility for the uncommodifiable – things the market cannot supply, price or deliver, and things it never has supplied, priced or delivered. That, I will argue, becomes ever more important as we enter an age of anthropocenic environmental catastrophism.

In short and to conclude this section, Esping-Andersen does not take enough account of the market failure that uninsurable risk represents, and he undersells the contribution of the welfare state to collective risk management in the process. He has, it might well be argued, an overly contractual view of the welfare state (which he no doubt inherits from T.H. Marshall, the English sociologist who developed the notion of ‘social citizenship’ to complement civil and political rights). For there is no clause in the citizenship contract that gives to the citizen the right to claim against the state in the last resort and/or in the face of uninsurable risk (when the market fails). That part of the contract is, at best, implicit. And it has tended to be overlooked for precisely that reason. But, in the final analysis and in the last resort, that is what matters; and in an age of anthropocenic environmental catastrophism is matters more and more.

The ‘New Orleans effect’ and the new fiscal crisis of the welfare state

So what are the implications of the above for an analysis of the recent past, present and future of the welfare state?

The first thing perhaps to note here is that it is only in the ‘lonely hour of the last instance’16 – the last resort, in other words – that Esping-Andersen’s contractual view of the welfare state becomes problematic. In 1990, when The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism was published, and for as long as the ‘great moderation’ persisted, the state’s willingness to insure citizens against uninsurable risk was of no great practical or theoretical importance. There were no ‘exogenous shocks’ to disrupt the expectations of comparative institutionalist political economists nor the path-dependent evolutionary trajectories of the welfare capitalist types to which Esping-Andersen drew our attention. It was, accordingly, of no great importance that he or others had failed to consider what might happen were the proverbial shit to hit the proverbial fan.

Today, however, that looks like more of an oversight. As noted above, uninsurable risks are typically referred to in insurance policies as ‘acts of God’. In an age of environmental catastrophism, the God imagined in the euphemistic hyperbole of the insurance contract is becoming ever more active and more vengeful too. The state’s role as public good provider of last resort is, in the process, becoming less of a purely abstract and theoretical concern.

But this is, of course, not just a question of ‘acts of God’. First, as the very idea of the Anthropocene implies, if there is agency here it is ours and ours alone. Second, it was the global financial crisis, and the ending of the ‘great moderation’ that it represented, and not the advent of an age of environmental catastrophism, that first shattered the benign contextual assumptions of the comparative institutionalist political economy of the welfare state. And if any of those assumptions endured that first ‘exogenous shock’ they were further shredded by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Neither of these no less catastrophic episodes has anything to do with the dawning of an age of anthropocenic environmental catastrophism, or at least that is not my argument. But the new normalisation of the return to exogenous shocks that they seem to signify gives us an important clue as to what the age of anthropocenic environmental catastrophism might look like for the welfare state.

For what both the global financial crisis and Covid-19 show very clearly is the state’s role as a public good (and welfare) provider in adversity, above all in conditions of profound market failure. When all else fails, it is the state, and only the state, to which we all turn. And the state provides; its emergency reflex, it seems, is to provide. What both episodes show us, in effect, is what the implicit part of the public insurance contract contains – what the state would provide were the ‘last resort’ clause to be invoked. When the cash point machine provides no cash because the bank has been rendered insolvent (Northern Rock), the state provides liquidity; when the ontological security of the population requires lockdown and the activities of the productive economy are largely suspended, the state provides furlough. In the process, long-established governing conventions are at least temporarily suspended. The imperatives of sound economic governance – above all competitiveness, fiscal rectitude, the control of inflation, austerity and, indeed, governance by economic imperative more generally – are all abandoned in the name of an altogether more overriding and pressing imperative – to insure citizens against uninsured (and invariably uninsurable) risk.

This challenges what we think we know about the state. Philip Cerny’s competition state ceases being a competition state (in that it no longer promotes the competitiveness of the economy above all else);17 Wolfgang Streeck’s consolidation state ceases being a consolidation state (in that it abandons fiscal consolidation and turns on the taps);18 even Christopher Bickerton’s EU member state ceases being a member state (in that it closes, unilaterally and without consultation, its borders and suspends the free movement of peoples and goods). 19 In the lonely hour of the last instance our state turns out to be a welfare state after all – above all, in Cerny’s terms – a state that places the welfare of its citizens first and foremost.

But this does not necessarily endure. When exceptionalism gives way to normality, the conventional imperatives return – and with renewed vigour. Now at markedly higher levels of public indebtedness, it is the austerity and consolidation imperatives that come to trump all others. We move from the ‘fair weather Keynesianism’ of the crisis to hyper-austerity, even if the latter proves difficult to implement (not least as the desired reduction in the debt to GDP ratio is more difficult to achieve when the austerity measures designed to reduce public spending have a drastic effect on GDP). The effect of this is to reduce, for as long as austerity is in place, the generosity to citizens of conventional, contractual, welfare (to compensate for the accumulated cost of exceptional, discretionary, non-contractual welfare).

This period of hyper-austerity also fails to endure for long. Because, just as it is starting to be normalised and institutionalised, we have the pandemic, triggering a second period of exceptionalism. The fiscal taps are turned on once again, and public debt rises again to previously unprecedented levels (not least as the intervening period of austerity did little to reduce debt to GDP levels, due to its negative impact on growth).

It is not difficult to see that the pattern is the same. Nor, I think, is it difficult to see that if we conceive of welfare as social or collective insurance then the state’s public good provision of last resort in both of these episodes is the provision of a welfare function. If that is accepted, it has profound implications for the future of the welfare state as we enter a period of anthropocenic environmental catastrophism.

To see what those implications might be it is useful to develop an analogy: ‘the New Orleans effect’, as I will call it.

If we are, indeed, entering an age of environmental catastrophism, as almost all available climate models suggest, then it is credible to think that this will become manifest as a series of disruptive events of growing magnitude, increasing intensity and ever greater frequency. Such events, I suggest, are like a succession of hurricane impacts.

What is interesting and potentially instructive here about such an analogy – and it is important to emphasise that, in the final analysis, it is just that, an analogy – is that it gives us some time-series data to work with. Consider the US case: hurricanes, above all in large landmass economies with an extensive coastal range such as the US, are low-probability events in any given place in any given year, but they have always been reasonably high-probability events at the level of the federal economy considered holistically. But in a context of both global climate change and global warming, the probability of such events – at both the local and aggregate level – has been rising, as has the average intensity and severity of each event.

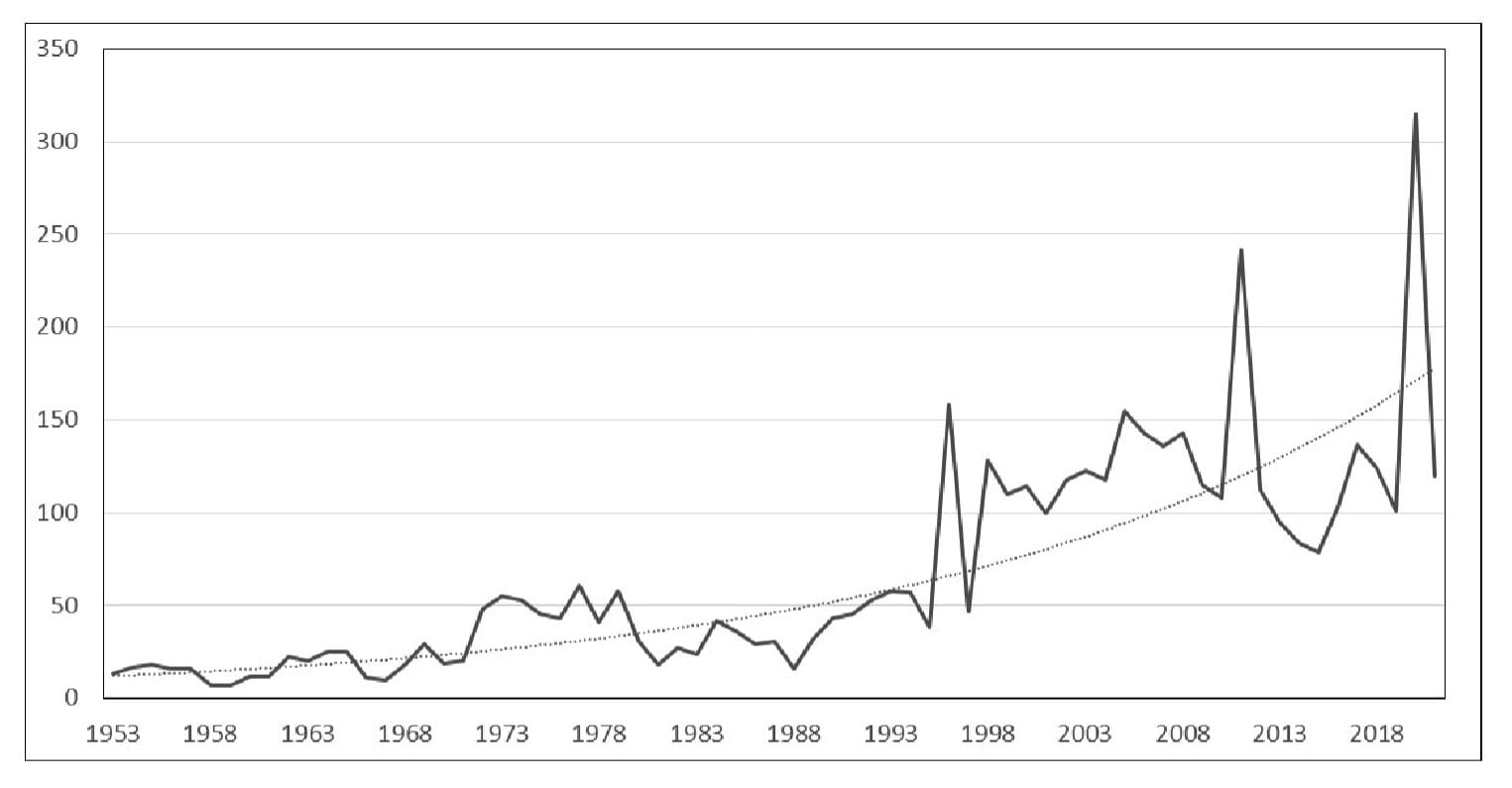

The graph below (Figure 1) shows, very simply, the number of official disaster declarations recorded by FEMA (the US Federal Emergency Management Agency) since the early 1950s.

Figure 1: FEMA disaster declarations, 1953-2022

The exponential increase in time is obvious. To give just a sense of what that might mean, in the year Esping-Andersen published The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism, FEMA recorded 43 disaster declarations. Thirty years later it recorded 315.

Alarming though that might be, however, it does not come close to capturing the social, political and economic implications of this increase. To begin to do that, it is necessary to consider the graph below (Figure 2).

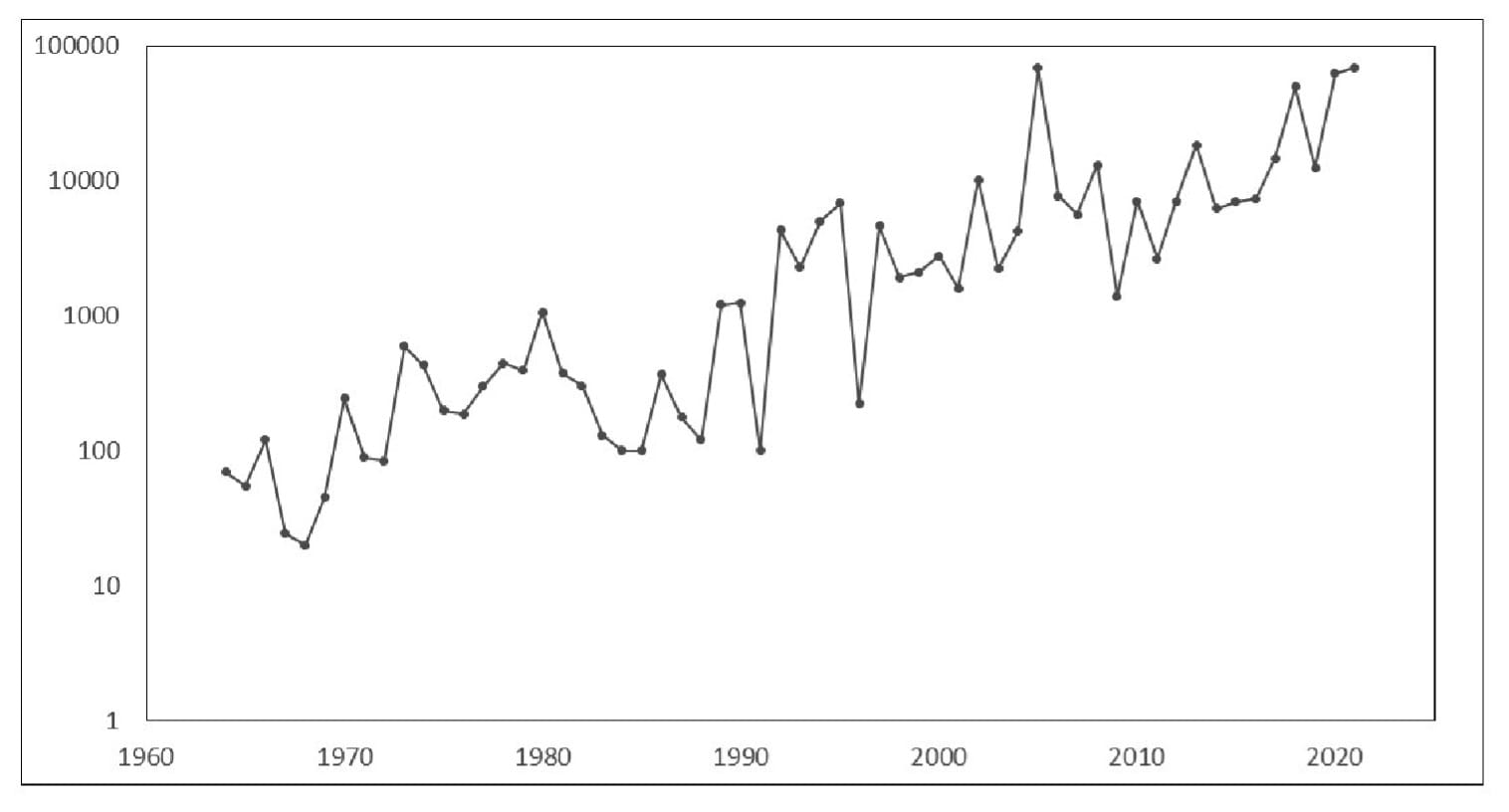

Figure 2: General US disaster relief appropriations ($US, nominal millions), 1964-2022 Source: calculated from US Congressional Research Service data, available at https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R45484

This shows not the number of declarations, but rather the cost of the disaster relief appropriations triggered (at the federal level) by such declarations – the cost to the taxpayer and, indeed, increasingly to the US’s creditors (as public debt levels have risen). The first available data is for 1964 (with annual disaster appropriations standing at a comparatively meagre $70 million US dollars at current prices).

This plot clearly makes for much more alarming reading. What it shows in effect – and in a way that gives us a powerful visualisation of the implications of current climatic models – is that this is not just a question of the increased probability of catastrophic events arising (of risk generating tangible harm). Crucially, it is also a question of the increasing average severity of each successive event series. Both the probability of harm and the scale of that harm have been increasing, and, in a context of accelerating and unchecked climate change, both continue to increase exponentially. Note that the y-axis here is an exponential scale. Interestingly, and no less alarmingly, US federal disaster relief appropriations in 2021 exceeded for the first time those of 2005 (the year of Hurricane Katrina), representing around 3 per cent of US GDP.

That may not sound like a lot, though it would of course represent quite a significant recalibration of current estimations of the size of the US welfare state. But, should the trend continue, US disaster relief by the mid-2030s is likely to exceed 20 per cent of current US GDP (although what actual US GDP would be in such a scenario is, of course, rather more difficult to estimate). Put differently, by that point it is likely to represent almost half of total US public expenditure. That does not seem credibly sustainable – and it is likely therefore to have very grave implications.

Note, too, that this is a significant underestimation of the actual cost to the US economy of environmentally-engendered disasters, let alone anthropocenic environmental catastrophism more generally. First, Figure 2 shows only Federal-level appropriations and not those at the state-level. Second, it takes no account of losses in taxation revenue arising from declared disasters such as Katrina.20Third, and as alluded to above, there is no attempt to consider the implications for the growth potential, growth rate or debt sustainability of the US economy. And, fourth, it gives no consideration to the consequences of climate change for resource and crop scarcity, supply chain disruption, healthcare costs, population displacement or any of the macroeconomic consequences arising from these factors and the various interaction effects between them (for inflation, interest rates and the cost of borrowing above all).

This is why is it perhaps best seen as an analogy rather than a model. Arguably it captures better the trend – and, above all, the exponential character of the trend – rather than the magnitude of the economic effect. But, such limits notwithstanding, its implications are brutally clear.

First, as we enter an age of anthropocenic environmental catastrophism the form and function of the welfare state is likely to change – with an ever-greater proportion of its total expenditure being, in effect, discretionary (the compensation of citizens for the harm arising from uninsurable risks) and an ever-diminishing proportion being contractual (the compensation of citizens for the harm arising from anticipated risks such as unemployment, ill-health or retirement).

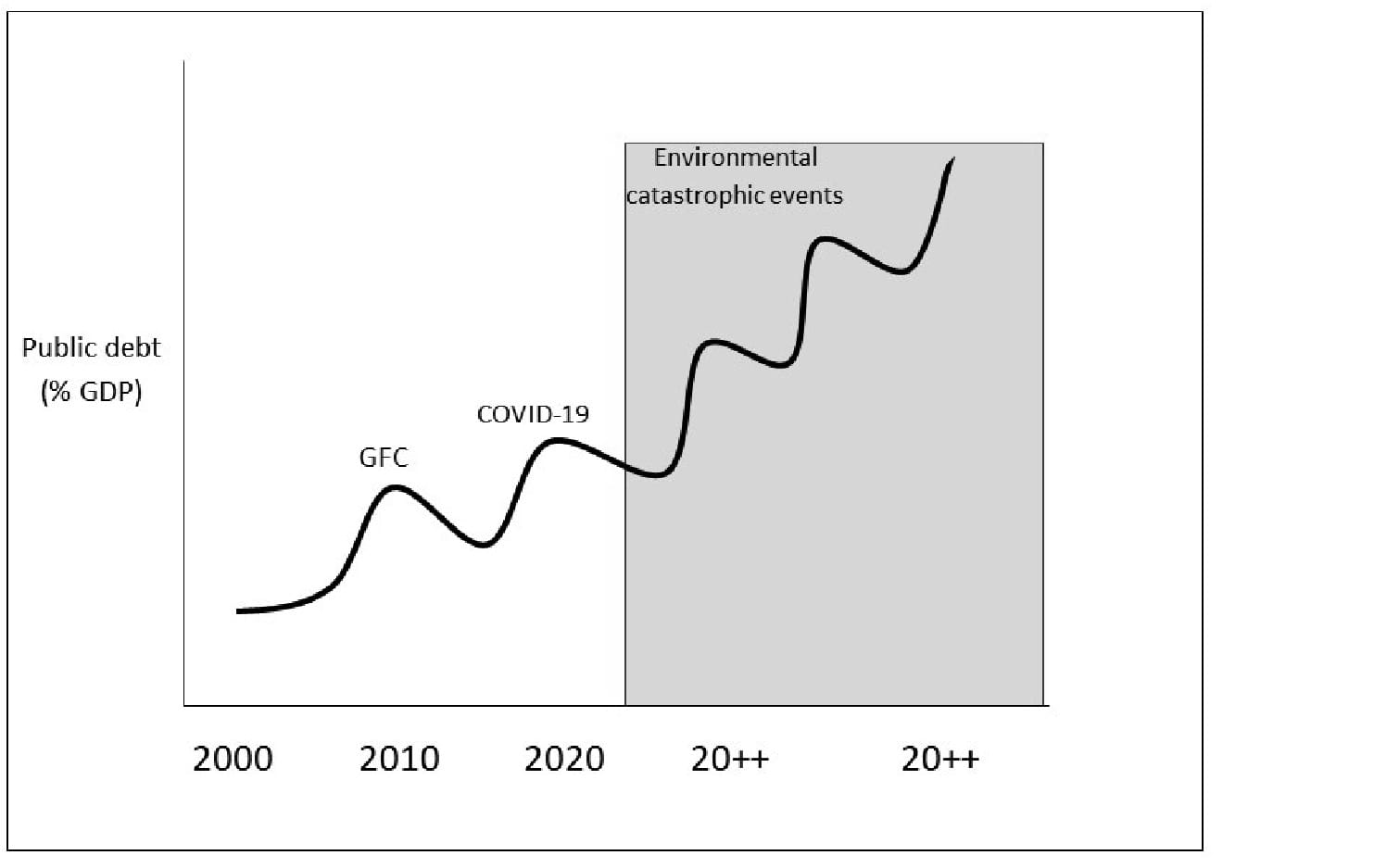

Second, the advent of an age of anthropocenic environmental catastrophism is likely to see an acceleration and intensification of the kind of debt amplification-debt reduction cycling that we have experienced since the global financial crisis – with ever-shorter periods of intense austerity punctuated, ever more frequently, by exceptional bouts of emergency-engendered deficit expenditure.

That suggests a second problem. In such an imagined future, aggregate debt levels (above all if expressed as a share of GDP, but even if expressed on a per capita basis) are likely to spiral – and from already unprecedented levels. For there is simply not enough time between crises, as it were, for austerity to compensate for the step-level increase in debt associated with insuring citizens (and indeed businesses) against the uninsurable risk represented by each catastrophic event. This is depicted schematically in Figure 3.

Figure 3: The debt amplification cycle

To return to a simpler analogy, more water runs through the taps in a crisis, when demand is being injected into the economy, than is saved through austerity in the (ever more limited) time between crises. The implication is immediately clear: the water (here figurative) runs out. What that means, in more practical terms, is that public indebtedness becomes unsustainable. Put starkly, the state’s risk of default itself becomes uninsurable. Generalised default risk becomes, in a sense, inevitable.

There is in fact a second possibility, which a more sustained exposition than is possible here would consider at somewhat greater length. It is that, in anticipation either of the likelihood of default or more simply that its creditors would call time on exorbitant and unsustainable levels of public debt, the state reneges on its own implicit contract with its citizens to act as their public good provider of last resort. In effect, the state in such a scenario, invoking the imperative of austerity, would defer the onset of fiscal crisis by imposing upon itself a form of legitimation crisis – a form of trade-off first envisaged in a rather different context by Jürgen

Habermas.21 It is not difficult to see that this ends no less badly. In Streeck’s terms it might ‘buy a little time’. But a state that refuses, in effect, to insure its citizens (and businesses) against uninsurable risk in a climatic emergency is unlikely to find it easy to continue to collect taxes at a level sufficient to hold off the prospect of the fiscal crisis it fears for long.

There is perhaps a third option too: that is for the state, in extreme fiscal adversity and in the context of an environmentally catastrophic emergency, to appeal to its neighbours and other members of the international community for assistance in disaster relief – externalising at least some of the costs in the process. That might sound like a credible and realistic strategy, and in more benign times it would be. But the closer one gets to a generalised condition of fiscal crisis, the less likely it is that multilateral assistance will be forthcoming.

In short, generalised debt default seems highly likely. Limits of space prevent a more elaborated reflection on what might unfold in such a scenario. But suffice it to note for now that the precise sequencing of events is crucial here. As noted above, environmentally catastrophic events are likely to continue to be distributed geographically in a highly uneven way (impacting most significantly high landmass continental economies, like the US, and those with high coast-to-landmass ratios, like the Maldives). These economies are then the most likely to reach effective fiscal overload first (regardless of their current debt to GDP ratios). They are in turn likely to pose the highest immediate risk of debt default. But the willingness of multilateral institutions to respond in a coordinated manner to the prospect of such imminent debt default, and to see that default risk as endemic rather than as an isolated problem is, in turn, likely to depend on the identity of the economy (or economies) in question. The prospect of African or Latin American debt default is not the same thing as the prospect of debt default in North America or Europe – even if the mechanism precipitating it is the same. It is likely to be responded to very differently.

Whatever happens in a such a moment and whatever the actual sequence of events turns out to be, ultimately a generalised fiscal crisis of the welfare state in the last resort seems almost inevitable. Fifty years after the first positing of the idea of such a fiscal crisis, it seems we have come full circle.22 But there is surely something profoundly ironic in the fact that the logic of fiscal crisis today should be driven by a factor that the original authors of the concept were scarcely aware of and, indeed, that has been ignored in the comparative political economy of the welfare state ever since. If there is one lesson of the thought exercise of this paper it is surely that it is finally time for the political economy of the welfare state to endogenise the environment and no longer to see it as capable of generating only exogenous shocks.

Conclusions

It is difficult to escape the pessimism of the above analysis. There is surely no more depressing a conclusion for a political analyst than a logic of inevitability: when things become inevitable, they cease being political. The very oxygen of politics is contingency.

But the account I have offered of the future of the welfare state as we enter an age of anthropocenic environmental catastrophism does have a series of practical policy implications, and those practical implications contain within them at least a glimmer of optimism. Let me conclude with just three of them.

First, the preceding analysis has sought to reveal the hidden part of the welfare state’s contract with its citizens – the hidden clause or clauses that apply in the lonely hour of the last instance, when there is nowhere else to turn other than to the state as the public good provider of last resort.

That the state continues to act as a public good provider in extreme adversity is itself reassuring and surely grounds for a certain optimism. It could be different; and in this respect at least, things could be worse. If the global financial crisis and the experience of the Covid-19 pandemic have shown us anything, it is that, however disaffected we as citizens have become with politics and the state, we continue to turn to it in adversity and it continues to reveal itself to be a welfare provider under such conditions. Indeed, and as I have argued, in adversity it turns out to be more of an unconditional welfare provider than it is in more benign conditions.

But as we enter an age of seemingly permanent crises (if not perhaps of permanent crisis per se), there is much to be said for the state (and those who wield state power on our behalf) being rather more explicit than they have previously tended to be about the currently implicit parts of the citizenship contract. When the lonely hour of the last instance is close, and in the face of uninsurable risks that are clear, obvious and known, there is perhaps no longer an excuse for keeping us in the dark about what we are (or will be) entitled to when known (environmental) risks produce actual (social and economic) harm.

Second, if the state (and those responsible for exercising power in its name) is to make a credible commitment to citizens in this way and to have any chance of substantiating that claim to be the public good provider of last resort in extremis, it becomes urgent to address at the multilateral level what happens when public debt becomes unsustainable. Above all it seems crucial to establish – and ideally, to enshrine in international law – the moral difference between a condition of potential debt default arising from (culpable) fiscal irresponsibility on the one hand and that arising simply by virtue of honouring a pledge (above all an explicit part of the citizenship contract) to insure citizens against uninsurable risk in the face of a climatic emergency.

Third, realistically, it is important to acknowledge that this is unlikely to be sufficient. The age we are entering, even in the above scenario, will see fiscal levees overwhelmed and the welfare state exposed in the last instance to a fiscal crisis that has been anticipated for over fifty years, though for a reason that is still not yet adequately integrated into the political economy of its form and functioning.

Interestingly, however, that throws the question back to political economy. For arguably the most crucial issue of our age is likely to turn out to be a question not of political ecology but of political economy after all – a question that pits political will against economic logic. It is a political economic question because the ecological die is already cast. The question is simply stated. Can debt proliferation, deft forbearance, and ultimately debt default be managed globally without destroying the capacity of the state as a public good provider of first and last resort, the global banking system, or both? We can only hope that the answer turns out to be a political one.

Colin Hay is Professor of Political Sciences at the Centre for European Studies and Comparative Politics, Sciences Po, Paris, and Affiliate Professor of Political Analysis in the Department of Politics, and Director of the Sheffield Political Economy Research Institute, at the University of Sheffield.

Notes

- P.J. Crutzen, ‘La géologie de l’humanité: l’Anthropocène’, Ecologie politique, Vol 34 No 1), 2007, pp141-148; S. Lewis and M. Maslin, ‘Defining the Anthropocene’, Nature, 519, 2015, pp171-180; W Steffen, Å Persson, L. Deutsch, J. Zalasiewicz, M. Williams, K. Richardson and U. Svedin, ‘The Anthropocene: From global change to planetary stewardship’, Ambio, 40, 2011, pp739-761; W. Steffen, J. Rockström, K. Richardson, T.M. Lenton, C. Folke, D. Liverman, H.J. Schellnhuber, ‘Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Vol 115 No 33, 2018, pp8252-8259.

- This is not to suggest that the dawning of the Anthropocene itself, and the pre-environmentally catastrophic phase of it through which we have been living, is not also significant for our understanding of the form, functioning and financing of the state (and, depending on the starting date chosen, the welfare state). It is, however, to suggest that as we enter a more catastrophic phase of the Anthropocene the need to consider the linkage between the political economy and political ecology of the welfare state grows (see M. Paterson, ‘The end of the fossil fuel age? Discourse politics and climate change political economy’, New Political Economy, Vol 26 No 6, pp923-936; and J. Green, ‘Comparative capitalisms in the Anthropocene: a research agenda for green transition’, New Political Economy, 2022, DOI:10.1080/13563467.2022.2109611. It is also to suggest that this linkage has as yet not been adequately grasped in the existing literature.

- A. Duit, P.H. Feindt, J. Meadowcroft, ‘Greening Leviathan: the rise of the environmental state?’, Environmental Politics, Vol 25 No 1, 2016, p2.

- Although see also D. Bailey, ‘The environmental paradox of the welfare state: the dynamics of sustainability’, New Political Economy, Vol 20 No 6, 2015, pp793-811; I. Gough and J. Meadowcroft, ‘Decarbonising the welfare state’, in J. Dryzek, R.B. Norgaard, D. Scholsberg (eds), Oxford Handbook of Climate Change and Society. Oxford, Oxford University Press 2011.

- Although see C. Hay, ‘Environmental security and state legitimacy’, Capitalism, Nature, Socialism, Vol 5 No 1, 1994, pp83-97.

- G. Esping-Andersen, The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism, Cambridge, Polity 1990.

- 7 C. Hay and D. Wincott, The Political Economy of European Welfare Capitalism, Basingstoke, Palgrave 2012.

- For a more general argument of this kind, see M. Paterson, ‘Climate change and international political economy: between collapse and transformation’, Review of International Political Economy, Vol 28 No 2, 2020, pp394-405.

- L. Baccaro and J. Pontusson, ‘Rethinking comparative political economy: the growth model perspective’, Politics & Society, Vol 44 No 2, 2016, pp175-207; A. Hassel and B. Palier (eds), Growth and Welfare in Advanced Capitalist Economies: How have Growth Regimes Evolved? Oxford, Oxford University Press 2021.

- In the sense that whilst ecological systems can be, and were once, preanthropocenic, economic and political systems cannot be and never have been pre-anthropocenic.

- The sole (and, in all likelihood, partial) exception to this is in the situation in which welfare types are geographically clustered and where exposure to the relevant environmental contingency co-varies with that clustering. If coastal flooding in the Mediterranean were the relevant contingency then one might expect it to reinforce in certain respects the ‘distinctiveness’ of the Southern European welfare regime type (certainly when compared to its Nordic or Anglo-liberal counterparts).

- C. Hay, ‘Does capitalism (still) come in varieties?’, Review of International Political Economy, Vol 27 No 2, pp302-319.

- Esping-Andersen, The Three Worlds, pp21-22.

- N. Barr, The Welfare State as Piggy Bank: Information, Risk, Uncertainty and the Role of the State, Oxford, Oxford University Press 2001; J. Meadowcroft, ‘From welfare state to ecostate?’, in J. Barry & R. Eckersley (eds), The State and the Global Ecological Crisis, Cambridge, MA, MIT Press 2005.

- Gough and Meadowcroft, ‘Decarbonising’, p491.

- L. Althusser, For Marx (trans. 1969, B. Brewster), Harmondsworth, The Penguin Press, 1965, p319.

- P.G. Cerny, ‘Paradoxes of the competition state: The dynamics of political globalization’, Government and Opposition, Vol 32 No 2, 1997, pp251-274.

- W. Streeck, Buying Time: The Delayed Crisis of Democratic Capitalism, London, Verso 2014.

- C. Bickerton, European Integration: From Nation-States to Member States, Oxford, Oxford University Press 2012

- For estimations of Katrina’s fiscal impact, see T. Deryugina, L. Kawano, S. Levitt, ‘The economic impact of Hurricane Katrina on its victims: Evidence from individual tax returns’, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, Vol 10 No 2, 2018, pp202-233; J. Vigdor, ‘The economic aftermath of Hurricane Katrina’, Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol 22 No 4, 2008, pp135-154; and, more generally, T. Deryugina, ‘The fiscal cost of hurricanes: Disaster aid versus social insurance’, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, Vol 9 No 3, 2017, pp168-198.

- J. Habermas, Legitimation Crisis, London, Heinemann 1976.

- Ibid; see also J. O’Connor, The Fiscal Crisis of the State, New York, St Martin’s Press 1973.